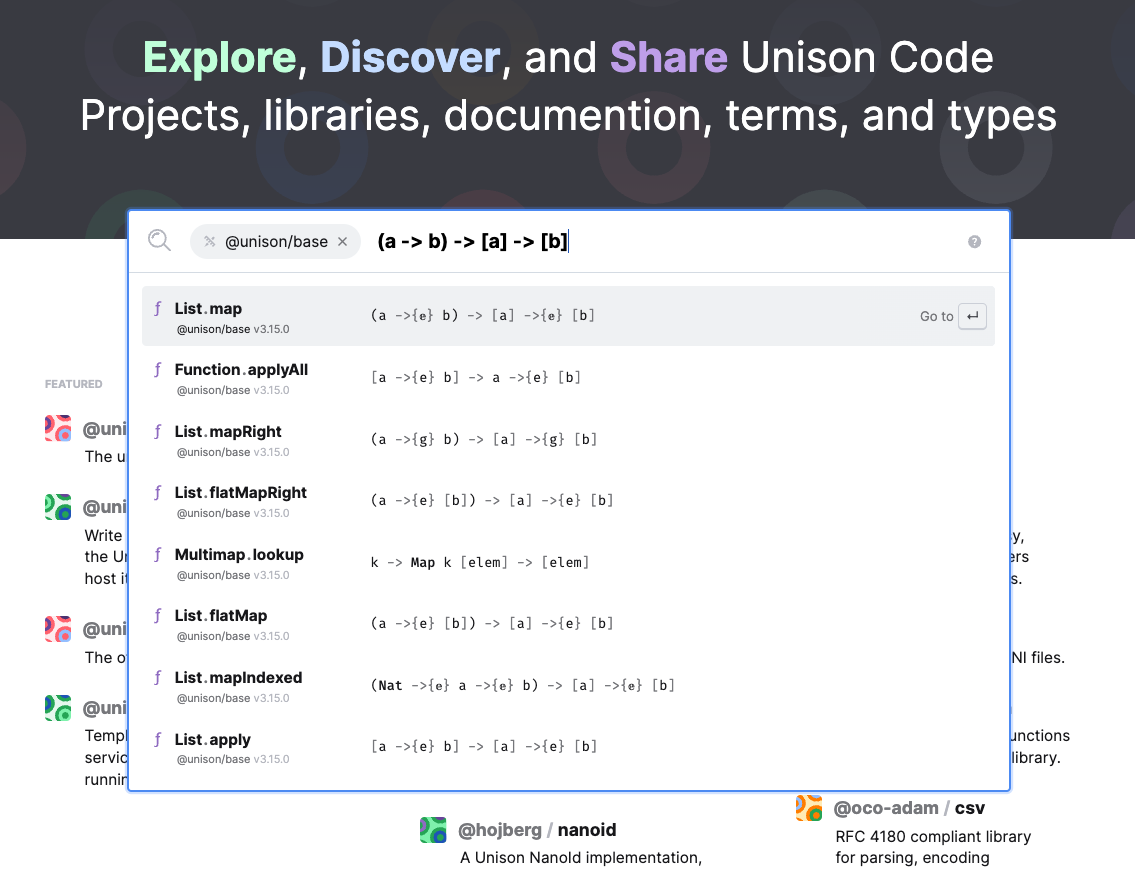

Hello! Today we'll be looking into type-based search, what it is, how it helps, and how to build one for the Unison programming language at production scale.

Motivating type-directed search

If you've never used a type-directed code search like Hoogle it's tough to fully understand how useful it can be. Before starting on my journey to learn Haskell I had never even thought to ask for a tool like it, now I reach for it every day.

Many languages offer some form of code search, or at the very least a

package search. This allows users to find code which is relevant for the

task they're trying to accomplish. Typically you'd use these searches by

querying for a natural language phrase describing what you want, e.g.

"Markdown Parser".

This works great for finding entire packages, but searching at the

package level is often far too rough-grained for the problem at hand. If

I just want to very quickly remember the name of the function which

lifts a Char into a Text, I already know it's

probably in the Text package, but I can save some time

digging through the package by asking a search precisely for definitions

of this type. Natural languages are quite imprecise, so a more

specialized query-by-type language allows us to get better results

faster.

If I search using google for "javascript function to group elements of a list using a predicate" I find many different functions which do some form of grouping, but none of them quite match the shape I had in mind, and I need to read through blogs, stack-overflow answers, and package documentation to determine whether the provided functions actually do what I'd like them to.

In Haskell I can instead express that question using a type! If I

enter the type [a] -> (a -> Bool) -> ([a], [a])

into Hoogle I get a list of functions which match that type exactly,

there are few other operations with a matching signature, but I can

quickly open those definitions on Hackage and determine that

partition is exactly what I was looking for.

Hopefully this helps to convince you on the utility of a type-directed search, though it does raise a question: if type-directed search is so useful, why isn't it more ubiquitous?

Here are a few possible reasons this could be:

- Some languages lack a sufficiently sophisticated type-system with which to express useful queries

- Some languages don't have a centralized package repository

- Indexing every function ever written in your language can be computationally expensive

- It's not immediately obvious how to implement such a system

Read on and I'll do what my best to help with the latter limitation.

Establishing our goals

Before we start building anything, we should nail-down what our search problem actually is.

Here are a few goals we had for the Unison type-directed search:

- It should be able to find functions based on a partial type-signature

- The names given to type variables shouldn't matter.

- The ordering of arguments to a function shouldn't matter.

- It should be fast

- It should should scale

- It should be good...

The last criterion is a bit subjective of course, but you know it when you see it.

The method

It's easy to imagine search methods which match some of the required characteristics. E.g. we can imagine iterating through every definition and running the typechecker to see if the query unifies with the definition's signature, but this would be far too slow, and wouldn't allow partial matches or mismatched argument orders.

Alternatively we could perform a plain-text search over rendered type signatures, but this would be very imprecise and would break our requirement that type variable names are unimportant.

Investigating prior art, Neil Mitchell's excellent Hoogle uses a linear scan over a set of pre-built function-fingerprints for whittling down potential matches. The level of speed accomplished with this method is quite impressive!

In our case, Unison Share, the code-hosting platform and package manager for Unison is backed by a Postgres database where all the code is stored. I investigated a few different Postgres index variants and landed on a GIN (Generalized inverted index).

If you're unfamiliar with GIN indexes the gist of it is that it allows us to quickly find rows which are associated with any given combination of search tokens. They're typically useful when implementing full-text searches, for instance we may choose to index a text document like the following:

postgres=# select to_tsvector('And what is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?');

to_tsvector

-------------------------------------------------------

'book':8 'convers':12 'pictur':10 'use':5 'without':9

(1 row)The generated lexemes represent a fingerprint of the text file which

can be used to quickly and efficiently determine a subset of stored

documents which can then be filtered using other more precise methods.

So for instance we could search for book & pictur to

very efficiently find all documents which contain at least one word that

tokenizes as book AND any word that tokenizes as

pictur.

I won't go too in-depth here on how GIN indexes work as you can consult the excellent Postgres documentation if you'd like a deeper dive into that area.

Although our problem isn't exactly full-text-search, we can leverage GIN into something similar to search type signatures by a set of attributes.

The attributes we want to search for can be distilled from our requirements; we need to know which types are mentioned in the signature, and we need some way to normalize type variables and argument position.

Let's come up with a way to tokenize type signatures into the attributes we care about.

Computing Tokens for type signature search

Mentions of concrete types

If the user metnions a concrete type in their query, we'll need to find all type signatures which mention it.

Consider the following signature:

Text.take : Nat -> Text -> Text

We can boil down the info here into the following data:

- A type called

Natis mentioned once, and it does NOT appear in the return type of the function. - A type called

Textis mentioned twice, and it does appear in the return type of the function.

There really aren't any rules on how to represent lexemes in a GIN index, it's really just a set of string tokens. Earlier we saw how Postgres used an English language tokenizer to distill down the essence of a block of text into a set of tokens; we can just as easily devise our own token format for the information we care about.

Here's the format I went with for our search tokens:

<token-kind>,<number-of-occurrences>,<name|hash|variable-id>

So for the mentions of Nat in Text.take's

signature we can build the token: mn,1,Nat.. It starts with

the token's kind (mn for Mention by Name), which prevents

conflicts between tokens even though they'll all be stored in the same

tsvector column. Next I include the number of times it's

mentioned in the signature followed by it's fully qualified name with

the path reversed.

In this case Nat is a single segment, but if the type

were named data.JSON.Array it would be encoded as

Array.JSON.data.,

Why? Postgres allows us to do prefix matches over tokens in

GIN indexes. This allows us to search for matches for any valid suffix

of the query's path, e.g. mn,1,Array.*,

mn,1,Array.JSON.* or mn,1,Array.JSON.data.*

would all match a single mention of this type.

Users don't always know all of the arguments of a function they're looking for, so we'd love for partial type matches to still return results. This also helps us to start searching for and displaying potentially relevant results while the user is still typing out their query.

For instance Nat -> Text should still find

Text.take, so to facilitate that, when we have more than a

single mention we make a separate token for each of the

1..n mentions. E.g. in

Text.take : Nat -> Text -> Text we'd store both

mn,1,Text AND mn,2,Text in our set of

tokens.

We can't perform arithmetic in our GIN lookup, so this method is a workaround which allows us to find any type where the number of mentions is greater than or equal to the number of mentions in the query.

Type mentions by hash

This is Unison after all, so if there's a specific type you care

about but you don't care what the particular package has named that

type, or if there's even a specific version of a type

you care about, you can search for it by hash: E.g.

#abcdef -> #ghijk. This will tokenize into

mh,1,#abcdef and mh,1,#ghijk. Similar to name

mentions this allows us to search using only a prefix of the actual

hash.

Handling return types

Although we don't care about the order of arguments to a

given function, the return-type is a very high value piece of

information. We can add additional tokens to track every type which is

mentioned in the return type of a function by simply adding an

additional token with an r in the 'mentions' place, e.g.

mn,r,Text

We'll use this later to improve the scoring of returned results, and

may in the future allow performing more advanced searches like "Show me

all functions which produce a value of this type", a.k.a. functions

which return that type but don't accept it as an argument, or perhaps

"Show me all handlers of this ability", which corresponds to all

functions which accept that ability as an argument but don't

return it, e.g. 'mn,1,Stream' & (! 'mn,r,Stream').

A note on higher-kinded types and abilities like

Map Text Nat and a -> {Exception} b, we

simply treat each of these as its own concrete type mention. The system

could be expanded to include more token types for each of these, but one

has to be wary of an explosion in the number of generated tokens and in

initial testing the search seems to work quite well despite no special

treatment.

Mentions of type variables

Concrete types are covered, but what about type variables? Consider

the type signature: const: b -> a -> b.

This type contains a and b which are

type variables. The names of type variables are not important

on their own, you can rename any type variable to anything you like as

long as you consider its scope and rename all the mentions of the same

variable within its scope.

To normalize the names of type variables I assign each variable a

numerical ID instead. In this example we may choose to assign

b the number 1 and a the number

2. However, we have to be careful because we also

want to be indifferent with regard to argument order. A search for

a -> b -> b should still find const! if

we assigned a to 1 and b to

2 according to the order of their appearance we wouldn't

have a match.

To fix this issue we can simply sort the type variables according to

their number of occurrences, so in this example a

has fewer occurrences than b, so it gets the lower variable

ID.

This means that both a -> b -> b and

b -> a -> b will tokenize to the same set of tokens:

v,1,1 for a, and v,1,2,

v,2,2, and v,r,2 for b.

Parsing the search query

We could require that all queries are properly formed type-signatures, but that's quite restrictive and we'd much rather allow the user to be a bit sloppy in their search.

To that end I wrote a custom version of our type-parser that is

extremely lax in what it accepts, it will attempt to determine the arity

and return type of the query, but will also happily accept just a list

of type names. Searching for Nat Text Text and

Nat -> Text -> Text are both valid queries, but the

latter will return better results since we have information about both

the arity of the desired function and the return type. Once we've parsed

the query we can convert it into the same set of tokens we generated

from the type signatures in the codebase.

Performing the search

After we've indexed all the code in our system (in Unison this takes only a few minutes) we can start searching!

For Unison's search I've opted to require that each occurrence in the query MUST be present in each match, however for better partial type-signature support I do include results which are missing specified return types, but will rank them lower than results with matching return types in the results.

Other criteria used to score matches include: * Types with an arity

closer to the user's query are ranked higher * How complex the type

signature is, types with more tokens are ranked lower. * We give a

slight boost to some core projects, e.g. Unison's standard library

base will show up higher in search results if they match. *

You can include a text search along with your type search to further

filter results, e.g. map (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

will prefer finding definitions with map somewhere in the

name. * Queries can include a specific user or project to search within

to further filter results, e.g. @unison/cloud Remote

Summary

I hope that helps shed some light on how it all works, and perhaps will help others in implementing their own type-directed-search down the road!

Now all that's left is to go try out a search or two :)

If you're interested in digging deeper, Unison Share, and by-proxy the entire type-directed search implementation, is all Open-Source, so go check it out! It's changing and improving all the time, but this module would be a good place to start digging.

Let us know in the Unison Discord if you've got any suggested improvements or run into any bugs. Cheers!

Hopefully you learned something 🤞! If you did, please consider joining my Patreon to keep up with my projects, or check out my book: It teaches the principles of using optics in Haskell and other functional programming languages and takes you all the way from an beginner to wizard in all types of optics! You can get it here. Every sale helps me justify more time writing blog posts like this one and helps me to continue writing educational functional programming content. Cheers!